Alan Burnett’s photo prompt for this week’s edition of

Sepia Saturday is a most atmospheric postcard view of the interior of a building in Oxford, taken from the collection of the

Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library Archives. Forgive me if I reproduce a portion of it here, but it is particularly germane to my own submission.

Although the precise location is not immediately evident, it seems to be an orchestra room in the Town Hall, with a large pipe organ forming a grand backdrop. There are eighteen men seated and standing around the room, apparently watching the final play in a game of snooker or billiards. Apart from the postcard’s caption, which refers to the 3rd Southern General Hospital, the main clue to who these men are lies in their clothing. Six of the men are wearing ordinary suits, the remaining twelve are garbed in what are generally termed “hospital blues.”

An image of this postcard view is included within the

Oxfordshire County Council’s Photographic Archive, the location described as St Aldate’s, Oxford, and a further view which includes the billiards table on the stage in the background demonstrates that the entire Town Hall was converted, even the stalls. The Woodrow Wilson Archive has a

similar view with somewhat better definition. A

post on the Great War Forum suggests that the Town Hall Section had 205 beds reserved for malaria cases amongst the Other Ranks. The single stripe on the arm of the man about to strike the ball with his cue confirms that he was a Lance Corporal, and indeed an “other rank.”

"I look pretty thin, Eh!"

Paper print, Collection of Barbara Ellison, Coloured by Andre Hallam

My grandfather

Charles Leslie Lionel Payne (1892-1975) and his younger brother

Harold Victor Payne (1898-1921) both spent time wearing hospital blues. My grandfather served in the

Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), having immigrated to Canada in 1912, initially with the

Canadian Army Service Corps (CASC) and then with the

Canadian Machine Gun Corps (CMGC). Harold joined the British Army in England towards the end of the war and served with the

Tank Corps. The photograph above, accurately coloured by Andre Hallam with the expert historical assistance of various members of the

Great War Forum, shows Harold (sitting at centre) and friends wearing hospital blues at an unknown location. “

I look pretty thin, Eh!” is handwritten in pencil on the reverse.

"Wounded Soldiers - I've met 'em. Yes sir."

Paper print, Collection of Barbara Ellison

Unfortunately his British Army service documents did not survive the Blitz - some 60% of the British Army’s

Great War service records were destroyed by German bombs in 1940, and the remainder badly damaged – so it is difficult to be sure of his movements. A postcard sent to his family in Derby in November 1919 shows that he was then "

in Cologne awaiting demob[ilization]" from the British Army on the Rhine (BAOR), was “

quite well” and recorded hopefully, “

guess I shan’t be long now.” I suspect that he took ill shortly after, before he could be demobilised. He died on 1 May 1921 at Derby. His mother was devastated, and although she would outlive him by a decade, I get the impression that she never really recovered from the shock. I have yet to order his death certificate, which may provide clues to his illness, and state whether or not he was still in the Army at that time.

Sgt. Leslie Payne, Winter 1918/1919

Paper print, Collection of Barbara Ellison

Sgt. Leslie Payne, CMGC, Winter 1918/19, in England or Canada

My grandfather’s CEF service records, on the other hand, have survived more or less intact although, sadly, I have no photographs of him wearing hospital blues. The portrait above, in which he wears his army greatcoat adorned with sergeant’s stripes, was probably taken in the Winter of 1918/19, after his recuperation had ended. I obtained a copy of his records from the

Library & Archives of Canada some years ago. From this treasure trove of shorthand scribblings, indecipherable abbreviations and obtuse acronyms, and together with transcripts of the

CMG Corps history and the

War Diaries for his unit, I was eventually able to piece together a detailed itinerary of his movements.

Constance May Hogg, Christmas 1913

Postcard, Collection of Barbara Ellison

By the spring of 1918, my grandfather had been in the Canadian Army for almost three and a half years, two and a half years of this on the Western Front, and two years as a machine gunner. He had fought at the Battles of

St. Eloi Craters (April 1916),

Mount Sorrel (June 1916),

Flers-Courcelette (September 1916),

Vimy Ridge (April 1917),

Lens (June 1917) and

Passchendaele (November 1917) and appears to have survived unscathed – at least physically - with not a single day of sickness or other misadventure recorded. During a period of rest and recuperation Leslie was granted two weeks of leave on 26th November, and he lost no time in heading home. Four days later, having been granted permission to do so by his Commanding Officer, he married his sweetheart “Con” at Chester, and was back with his unit by 14th December.

Canon de 380 m/m capturé par les Australiens près de Chuignes et destiné au bombardement d'Amiens

Postcard with 1930 postmark, Collection of Barbara Ellison

On 20th April 1918, as part of the overall reorganization of the CMGC being undertaken at that time, Leslie was promoted to the rank of Sergeant, and thus put in charge of a machine gun section, comprising two Vickers machine guns with crews. On 9 July he was sent to the Canadian Corps School on a four week long training course. He probably returned to his unit just in time to participate in the very successful

Battle of Amiens, on 8th, 9th and 10th August.

AMIENS - AUG 11 1918 - STATION PLATFORM BUFFET

Paper doily, Collection of Barbara Ellison

No. 2 Company of the 2nd Battalion CMGC was relieved and withdrawn from the line into reserve at Caix, allowing Leslie and his crew to enjoy the luxury of real food in Amiens on the evening of 11th August. After a week of rest, during which time the ranks were brought back up to strength by very welcome, but green, reinforcements, the entire Canadian Corps was moved back to the Arras Front. Leslie’s company arrived at their billets in the village of Monts-en-Ternois at noon on the 21st, and was bussed to the front lines the following day.

According to the corps history, the massive task of the Canadian Corps was to drive in south of the Scarpe towards Cambrai, to break the Quéant-Drocourt Line and, once the Canal du Nord was reached, to swing southward behind the Hindenburg Line. No. 2 Company was, as usual, to be in support of the 6th Canadian Infantry Brigade on the right front, the attack scheduled for the 26th.

The machine gun crews were assigned positions on high ground near Telegraph Hill, from where they would form part of a series of 16 batteries putting up a creeping barrage of indirect fire to cover the infantry’s advance. One machine gun was all0tted to every 35 yards of front. Zero hour was at 3 a.m., when the barrage commenced. By 6 a.m. reports of casualties and guns put out of action - by the German counter-barrage - were coming in from crews hampered by thick mist and smoke from the artillery barrage.

Testing a Vickers machinegun, September 1916

Image © and courtesy of Library & Archives of Canada

Some time during the day Leslie was hit in the left shoulder, probably by a machine gun bullet, although it could have been a piece of shrapnel. He was not the only one, the 2nd Battalion CMGC suffering its greatest number of casualties of any single attack in the war up to that point, with a total of 27 men killed and 183 wounded between 26th and 28th August. The CO’s report stated:

Lack of stretchers was very pronounced. In some cases our wounded lay out for over 12 hours and in all cases it was most difficult to evacuate our casualties or to attend to them in the absence of stretchers or bearers.

Hospital Ship Princess Elizabeth

Image © and courtesy of Ian Boyle/Simplon Postcards

He was stretchered first to the nearest first aid post or dressing station, then to No 42 Casualty Clearing Station, where it was ascertained that the "foreign body" was still lodged in his shoulder. Later that day he was evacuated to No 4 General Hospital in Camiers, on the coast. As soon as space could be found in the transports, he was shipped across the Channel aboard the Hospital Ship

Princess Elizabeth, a converted Isle of Wight paddle steamer, arriving at the County of Middlesex War Hospital, Napsbury St Albans on 30th August.

An examination at Napsbury the following day is reported on his Medical Case Sheet, in the usual almost indecipherable handwriting:

Entry 2" internal to point of acromion. F.B. (Foreign Body] palpable mid way between this + axilliary fold on post surface. Clean.

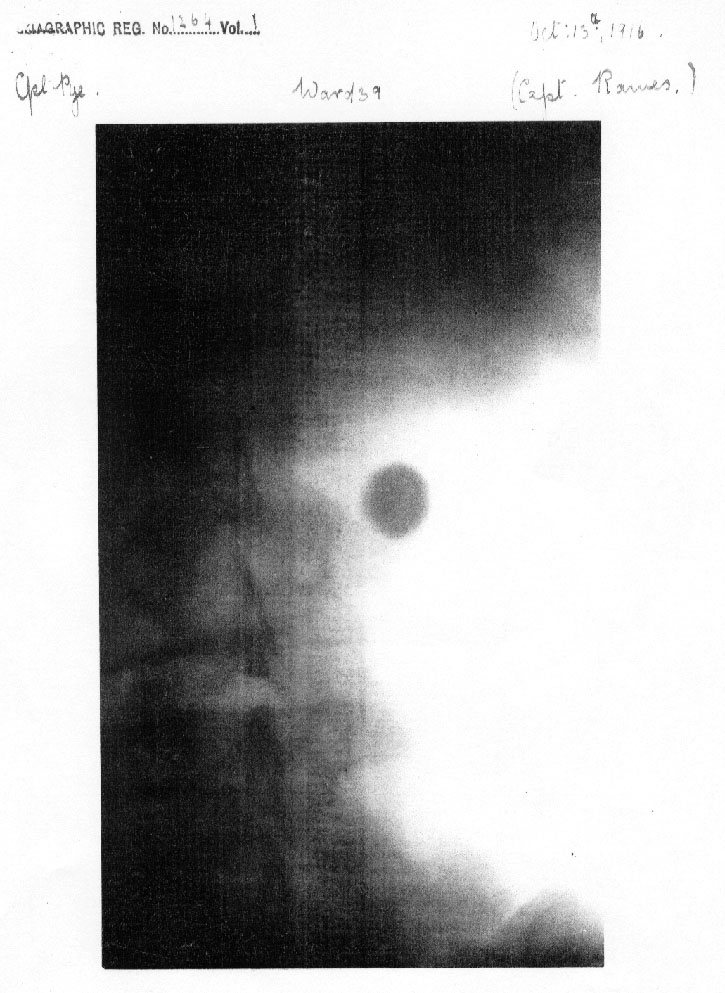

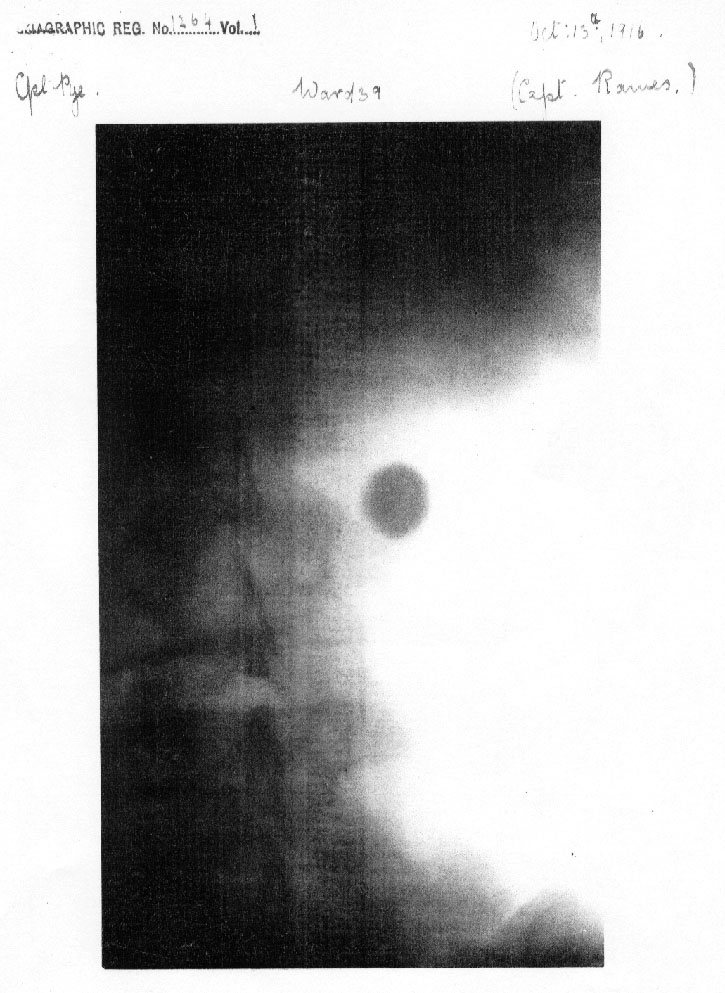

An X-ray examination report described a "

Bullet present subcutaneous," and a notation makes it clear that he was a "walking," rather than "stretcher" or "chair," patient. Although no X-ray image appears to have survived in his records, the image of a skiagraphic above, extracted from a fellow soldier’s service record, shows a similar lodged bullet. On 6th September an operation was conducted and the doctors successfully removed the offending piece of lead.

Patients and nurses at Napsbury St Albans, 1917

Image © Rohan Price and courtesy of Hertfordshire Genealogy

The subsequent entries on his medical records indicate that he "

returned from auxilliary, healed" on 4th October, and was discharged to the Canadian Military Convalescent Hospital at Woodcote Park, Epsom three days later. He was given a final medical examination on 8th October which pronounced him fit “Di” and, after recuperating for another week, he was discharged on Monday 14th and sent on furlough for ten days.

154 Almond Street, Normanton, Derby

Image © & courtesy of Google Maps Street View

Of course Leslie headed straight home to Derby but when he arrived he found Con very ill. She succumbed to influenza at 154 Almond Street, Normanton, Derby on Sunday 20th October. It was the second major wave of the “Spanish”

flu epidemic in the United Kingdom, with hundreds of thousands dying, and Leslie’s distress during the journey back to the Canadian Machine Gun Depot at Seaford, Sussex on the 24th must have been acute. The regulation requirement to report to the Paymaster that his wife was deceased, and therefore he was no longer entitled to separation pay, would no doubt have added insult to injury, the loss of $25 a month being the least of his concerns.

At 11 a.m. on 11th November 1918, the day that Leslie received his final TAB inoculation, the armistice between the German and Allied Forces came into effect, and the war was suddenly over. Without Con, Les must have looked at peace time with mixed emotions. Who knows what their plans had been? Would they have gone back to Winnipeg together, where Leslie had a decent clerk’s job at Eaton’s department store waiting for him? It seems likely. He was eventually demobilised in Canada in February 1919, after a prolonged stay at Kinmel Park in Wales and a trip across the Atlantic on the S.S.

Olympic, but that’s a story for another time.

Leslie Payne, Summer 1915 (left) and Winter 1918/19 (right)

Paper prints, Collection of Barbara Ellison

I find it telling how much he changed in that short space of time. He was a fresh-faced 22 year-old when he enlisted in the CEF in November 1914, and a haggard 26 on discharge. He looks at least a decade older in the later photo, not just three or four years, and I’m sure it was not just his appearance that was different. I've been told that Grandpa hardly ever talked about the war, at least not to anyone who ever felt comfortable to share such confidences with others, and from what I can tell this was not uncommon amongst Great War veterans.

How should he communicate and explain such a kaleidoscope mish-mash of contradictory emotions and experiences in which they had been suddenly immersed on the Western Front, in Leslie’s case, for 2 years, 11 months and 14 days? Their subjection, after rudimentary initial training, to a totally unfamiliar environment, the exhausting slog of marching and carrying supplies to the front, the tedium and discomfort of life in the trenches, the camaraderie eventually engendered between members of a machine gun crew who lived every moment of every day together, often within inches of each other, for months on end, and the anticipation of death at any moment, from any quarter, in the trenches, eventually replaced with mind-numbing resignation – all these would have been incomprehensible to their families and friends back home.

I hope that he was eventually able to dispel at least some of the dark thoughts, but I am sure there were many others that he could never forget. And nor should we.