This challenge required some considerable background reading on my part, but the subject is of particular interest to me. Not only was I involved in the gold exploration industry for some fifteen years, but I've long had a fascination with historic gold rushes and the motley cast of characters who often played a part in them, such as the Californian forty-niners (1849), the Witwatersrand uitlanders (1886) and the Klondike stampeders (1897).

Print by Burton Brothers, Dunedin

Image © and courtesy of National Gallery of Australia

Accn No: NGA 2007.81.119AB

Prior to the 1860s the West Coast of New Zealand's South Island was an almost completely uninhabited no-man's land, the steep forest-encrusted and almost inpenetrable slopes and rocky, surf-pounded coasts with few natural harbours discouraging all but a few passing explorers. Maori visitors, who succeeded in extracting prized pounamu from the river valleys and mountain peaks, and pakeha whalers briefly occupied a few temporary shore stations, but neither group left much in the way of permanent settlements. District boundaries tended to be merely lines drawn on the maps by the colonial state authorities with little real meaning on the ground. In 1861 Charles Hursthouse described it as "a savage, gloomy country, silent, desolate and dreary ... this vast tract is unpeopled; millions of acres have never been trodden by human foot ... fresh from nature's rudest mint, untouched by hand of man.," but then went on to predict with pinpoint accuracy the forthcoming means of change: "... this part ... has as yet been very partially explored ... [but] may prove to be New Zealand's 'Gold Coast'." [1]

Wood engraving published in The Illustrated Australian News

Image © and courtesy of State Library of Victoria

Accession no IAN10/07/76/104

Between 1865 and 1867 a sequence of events shattered this isolation forever. In the early 1860s the province of Otago, situated on the other side of the Southern Alps, had experienced a gold rush the likes of which had never before been seen in New Zealand. As individual diggings like Gabriel's Gully suffered declining yields of the royal metal, prospectors looked further afield towards the West Coast, walking overland through the dripping, verdant forests and exploring by boat the shingle beaches and rivers along the wild, rocky coast. [2]

Albumen print, 120 x 200 mm, on album page

Image © Alexander Turnbull Library and courtesy of Timeframes

Reference No. PA1-q-069-02-1

On the 27th February 1865 the landing in Nelson of an single enormous shipment of gold from diggings at Hokitika, equal to the entire production from the previous year, precipitated a tremendous rush. Within a matter of weeks word had spread, not only to Wellington, across the Cook Strait, and more distant provinces such as Canterbury and Otago, but also across the Tasman to Victoria and New South Wales. Diggers braved the wild seas, cramming every available sea-going vessel, and travelled to the new finds by any means they could find. Settlements began to spring up in the Waimea Valley, Okarito, Greymouth and the Pakihi, between the Buller and Grey Rivers. [3]

Image © Alexander Turnbull Library and courtesy of Timeframes

Reference No. 1/2-055911-F

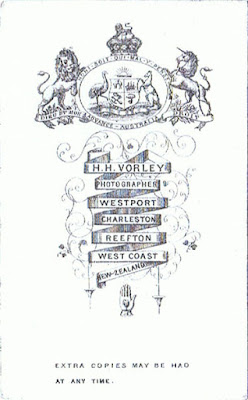

Almost overnight clusters of scruffy tents mushroomed into bustling towns with narrow streets, elaborate wooden buildings, hotels and dancing girls. [4] Perhaps the greatest of these in the history of the West Coast was the Charleston rush, reaching a peak between 1867 and 1870 with a population of around 5,000. [5] Boats bringing in both prospectors and supplies braved the narrow and treacherous entrance to the tiny Constant Bay, with wrecks and tragedy a common occurrence. [6]

Charleston, West Coast, New Zealand

Image © and collection of Brett Payne

One of the many hundreds of people who set up shop in Charleston to take advantage of the tremendous increase in trade was photographer Herbert H. Vorley. [7] Although born to a wealthy merchant family in London he emigrated to New Zealand in the mid-1860s, arriving on the West Coast and setting up as a photographer and phrenologist in the town of Westport prior to 1867. While maintaining this studio, he is also known to have operated branch studios in Charleston (1867, 1869, 1873 & 1875), Hokitika (1870), Buller (1874 & 1877) and Reefton (1877-78). [8]

Image © National Library of New Zealand and courtesy of Papers Past

It seems likely from the nature of advertisements in the Grey River Argus, the West Coast Times and the Inangahua Times between 1875 and 1878 that the branch studios were open only intermittently, and on occasion staffed by managers or employees. A detailed examination of back issues of the Charleston Herald - sadly not yet included in Papers Past, the National Library of New Zealand's otherwise comprehensive digital coverage of old newspapers - may be they key to determining more precisely the dates of Vorley's presence in Charleston. [9] An inheritance received after the death of an English aunt in January 1879 enabled Vorley and his family to leave Westport in May that year and return to England, where he died a year later. [10]

Image © University if Southern California Regional History Center, CHS/TICOR Collection and courtesy of the History Computerization Project

The gold output of the Charleston area, in tune with the "boom and bust" cycles experienced in all of the other gold fields, was already waning by the early 1870s and the population dwindled rapidly, with many leaving to try their luck in newer fields such as Thames on the North Island. [3] Other enterprising diggers remained in the area and a large and well documented group of Scots from the Shetland Islands turned their hand to washing gold at Nine-Mile Beach, a short distance north of Charleston. Although the alluvial beach deposits had been discovered and worked by other beachcombers using fairly primitive methods a few years earlier, the first of the Shetlanders to arrive, in January 1870, were Magnus Mouat and Gilbert Harper from the village of Norwick on the northernmost island of Unst. [11]

Lantern Slide

from Chips of the Auld Rock publ. 1997

Image © and courtesy of Wellington Shetland Society

Having spent a couple of years wandering the Queensland, New South Wales and Bathurst gold fields and eight months at Bradshaw's Creek near the Buller River with little to show for their efforts, the auriferous black sands at the southern end of Nine-Mile Beach appeared to offer more promise. [11] So much, it appears, that sent word to other members of the original Unst party who had wandered elsewhere in Melbourne and Otago, and wrote to friends and family back home in Unst.

© Copyright Mike Pennington, courtesy of Geograph.co.uk

& licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

A dwindling of traditional fishing and farming opportunities, as well as clearances in the Shetlands, coincided with timely offers of assisted passage from Sir Julius Vogel's recruitment drives and immigration schemes. [12] Over the next few years a large number of families joined them, such that by 1877 it was estimated that there were about a hundred Unstmen working the sands at Nine-Mile. In November 1875, the provincial government surveyor was kept very busy surveying new leases and extended claims on Nine Mile Beach. [13] Magnus Mouat himself went home for a couple of years, during which time he married, returning to the West Coast goldfields with wife and baby aboard the Howrah in November 1876. [14]

(L-R) Magnus Johnson, John Madden, James Mouat, J.R. Mouat, Gilbert Harper & James Harper

Image © Alexander Turnbull Library and courtesy of Timeframes

Reference number: PAColl-6181-35

The Shetlanders were strong, practical men and soon improved their chances by purchasing most of the claims on Nine-Mile Beach and by developing new methods of extracting fine gold from the layers of black beach sands. Apart from the building of extensive tail races or flumes by Messrs. Hall, Parsons and Harle to bring to the beach the water so essential to the operation, already well under way by March 1872 [15][16], the Shetlanders made significant improvements to the washing process, designing the multi-tier mobile washing tables, or "beach boxes." These devices are illustrated in the images above and below, while the tail races are clearly visible in the background of the lower image.

William Harper (left) and John Mouat (right)

Image © Alexander Turnbull Library and courtesy of Timeframes

Reference number: 1/2-015698-F

The Charleston Herald (reported in the Grey River Argus) remarked on their good fortune although it was, no doubt, mixed in with decent proportion of hard slog:

1 December 1876

The beach claims in Second Bay and on the Nile and Nine-mile Beach, have for the past five or six months been paying exceedingly well. The men on Nine-mile Beach have been very fortunate, they having during the above-mentioned term been earning on an average from 25s. to 30s. per day.

6 July 1878

since the late stormy weather, accompanied by heavy south-west gales, the Nine-Mile Beach claims are paying splendidly, some of the miners who work long hours netting as much as £12 per man per week. It is said, and with a good deal of truth, that the mining property, dams included, sold some six years ago by Mr Fred Hall for the sum of four or five hundred pounds, to-day is worth as many thousands. This tells well in favour of the healthy condition of mining matters in this district.

13 August 1878

One of the beach claims which was only the other day taken upon the Nine-mile Beach, on the Northern limit, having hitherto being lying idle, was sold last week by Mr Thomas Humphries to Mr Sullivan for the sum of £50. At present there are more beachcombers at work on the Nine-mile Beach than has been remembered for the last six or seven years, and the lowest wages made by them is £3 and £4 per week, the highest being £10 and £12. The beach has "made" so much that the men are sure that payable ground exists to within close limits to the Totara river - a distance from the north claim, now work of about two miles. At present the water is not conveyed any distance along the beach, so that there is little probability of the ground now lying dormant being worked just yet, though we hear that it would be a very easy matter to bring water to the ground.

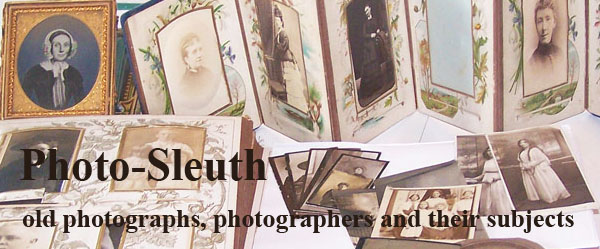

Carte de visite by H.H. Vorley of Westport, Charleston & Reefton

Image © and courtesy of Nola Sinclair

Nola Sinclair's husband's ancestor James Mouat Harper (1832-1918) arrived with his wife Margaret (née Anderson) (1836-1918) and eight children [17] in Nelson in January 1876, after a three month trip from Unst. They were part of a large group aboard the Caroline making their way to Charleston where a great Unst reunion was subsequently held. [11] The carte de visite portrait shown above depicts a large group of nine men, women and children standing in front of a wooden building, with a backdrop of moderate sized trees. The house has a cylindrical water tank, apparently for collecting water off the roof via the visible gutters and down-pipes, and a timber(and corrugated iron?)-encased chimney to the left. There is also a wood picket fence in the right foreground, possibly enclosing a vegetable garden.

Carte de visite by H.H. Vorley of Westport, Charleston & Reefton

Image © and courtesy of Joan Robertson

Nola also sent me this image of another carte de visite, which she had received from Joan Robertson, a distant cousin of her husband's still living in the Shetlands. It is very similar, although not identical, to the one that Nola has in her collection.

Detail of carte de visites by H.H. Vorley

Image © and courtesy of Nola Sinclair

A comparison of detailed scans elucidates some differences: most of the figures have moved slightly, and in the second shot there is an additional male adult figure standing immediately to the right of the doorway. The only adult female is standing at the extreme left of the group. The youngest of the children, standing at second from left, is perhaps three or four years old; the clothes suggest a little girl - although one cannot be certain at this young age - who is holding his or her mother's hand. The figure to the right of this is almost certainly a boy, wearing a cap and long trousers, and probably five or six years old. Next are two girls, aged about 8-9 and 10-11, respectively. To the right of the doorway a further group of three girls are fairly similar to each in height - almost the height of the adult woman at extreme left - so it is difficult to estimate their ages beyond saying that they are probably in their mid- to late teens. They all have their hair in a style typical of the 1870s, partly in plaits tied up in a circlet on the crown, and partly descending in ringlets to the shoulders at the back.

All three men are bearded and wearing hats. I would suggest that the man to the left of the doorway, wearing a waistcoat, is older while the two to the right are somewhat younger, but it is difficult to be precise. The men to the left and right are wearing bowler hats, of a style with a moderately high brow which was common through the 1870s and early 1880s. The man in the middle has what appears to be a forerunner of the wider flat-brimmed slouch hat, and is wearing a jacket.

The reverse of the second carte de visite (shown below) is inscribed, in what appears to be a contemporary hand, "to Anthony." Nola tells me that the second photograph was a copy mailed back home to Anthony Anderson, great grandfather of Joan Robertson, possibly by Anthony's sister Margaret Yule Harper.

Image © and courtesy of Nola Sinclair

If this is the case, then she may have been the woman standing at the extreme left of the group, and the remaining figures would then include her husband James Harper and at least some of their children. She is dressed in clothes typical of of the mid- to late 1870s. The bodice is tight-fitting with a prominent vertical row of buttons, and a bow at her neck, while the sleeves are narrow, a little looser at the wrist, and possibly with a frilled or pleated cuff. Although not actually visible, the bustle in her skirt is probably small, if present at all, and the skirt contains several layers, types of fabric or ornamentation. Her hair is parted in the centre drawn back tightly, probably into a bun at the back of her head.

Two further children were born to James and Margaret after their arrival in New Zealand, bringing the total to ten [17]:

James Mouat HARPER (1832-1918) m: 1855 Margaret Yule ANDERSON (1836-1918)

- Charlotte b. 24 Jan 1857 Norwick, Unst

- William b. 29 May 1859 Norwick, Unst

- Elizabeth b. 15 Feb 1862 Braefield, Norwick, Unst

- Williamina/Wilhelmina b. 23 Aug 1864 Unst

- Margaret b. 23 Jun 1867 Velzie, Unst

- Jemima b. 16 Apr 1870 Unst, Unst

- Gilbert b. 3 Mar 1873 Velzie, Unst

- Ann b. 3 Jul 1875 Norwick, Unst

- Isabella b. 7 Jan 1879 Charleston, New Zealand

- Anthony b. 24 Dec 1881 Charleston, New Zealand

Image © and courtesy of Joan Robertson

The reverse of both card mounts have a design very similar to that of the Vorley carte de visite shown earlier, with the addition of studio locations in Charleston and Reefton, suggesting to me a slightly later date i.e. some time after c. 1870-72. We can be fairly sure, however, that the photographs were taken prior to May 1879, when Vorley left New Zealand for good. This rules out the possibility of the youngest child born to James and Margaret in New Zealand being in the photograph, since Anthony was born in December 1881. If height is used as an approximate indication of age, then the children in the photograph are arranged from left to right in increasing order of age.

Detail of carte de visite by H.H. Vorley

Image © and courtesy of Nola Sinclair

Now some theorising. If - and I agree with Nola that we should emphasize the 'if' - this were to be the Harper family, then the only young male child, aged approximately five in the photograph, must be Gilbert Harper, born in Unst on 3 March 1873, suggesting a possible date for the group portrait of 1878 or early 1879. How do the the ages of the remaining children and adults in the group fit with what we know about the Harper family? Well, I think they match very nicely. N.B. The numbers in the provisional list below refer to those shown in the silhouette index above.

1. Margaret Yule Harper née Anderson, aged 42ish - Margaret does not appear very pregnant in this photograph, and since she had her ninth child Isabella in January 1879, I suggest this is unlikely to have been taken in late 1878. It is conceivable, however, that it was taken after the birth of Isabella, and that the baby is asleep indoors.

2. Ann Harper, aged 3

3. Gilbert Harper, aged 5 - Gilbert died at Charleston on 14 March 1883, aged 10.

4. Jemima Harper, aged 8

5. Margaret Harper, aged 11 - although the top of Margaret's head is only slightly higher than that of Jemima, examination of her feet shows that she is standing in a slight dip, and is therefore somewhat taller than she appears in relation to her next youngest sister.

6. James Mouat Harper, aged 45 - James Harper's central position in the group and manner of standing with his feet slightly apart, hands crossed calmly and patiently in front of him, is commensurate with his status as head of the household.

7. This is probably a younger man, although the full beard does disguise the age to some extent. His is a youthful figure assuming a very relaxed pose, his legs crossed, leaning against the door jamb with his thumbs tucked into his belt, holding the flaps of his jacket open. The jacket may have fringe sleeves, in a "Western style." This is most likely to be William Harper, who would have been aged 19, and very much "at home."

8. Williamina Harper, aged 13 or 14

9 & 10. Elizabeth Harper, aged 16, and Charlotte Harper, aged 21

11. This man, perhaps a little older than the man postulated as William Harper, is standing well off to the right hand side of the others. With his elbow perched on the window sill and right hand to his cheek, he is facing and leans in towards the rest of the group, in contrast to all of the others, who look directly at the photographer and his camera. So, while he is clearly part of the group, one gets the feeling that he is somehow distanced from it, in both a physical and more social sense. The eldest Harper daughter Charlotte married James Harper Mouat (1849-1928) at Charleston on 3 May 1878, and my feeling is that this is young Mr Mouat. He would have been about 30 years old at the time, and the photograph may have been taken before the wedding - hence the distance between him and the Harpers. [17]

Lantern Slide

from Chips of the Auld Block publ. 1997

Image © and courtesy of Wellington Shetland Society

The house forming the backdrop in this group portrait looks very similar in shape and form to the second building along the beach in the 1886 view, as pictured in the detailed image above, although Nola has pointed out that the frieze of large trees behind the house has been removed.

So ... we can make several tentative conclusions:

(a) The carte de visite portrait was most likely taken between 1874 and 1879 at or near Westport, Charleston or Reefton on the West Coast of New Zealand.

(b) We have a possible identification of the house in the portrait as being one of those built by the Shetland community prior to 1886 on Nine-Mile Beach.

(c) The group shown matches very closely the Harper family that we expect to have been living at Nine-Mile Beach in 1878.

Although I feel we have a probable identification, to be more confident I would suggest examining the make up of the other Shetland families who were living at Nine-Mile Beach in the late 1870s, to see if any of them fit the pattern. Most of the families living there were fairly closely related, having emigrated from the same small district on the island of Unst, so it is conceivable that somebody else might have sent a copy home "to Anthony."

Image © Alexander Turnbull Library Ref. PAColl-6075-51

Courtesy of Matapihi - Alexander Turnbull Library, New Zealand

In the mid-1880s there were still between 70 and 80 Shetlanders working the sands at Nine-Mile Beach but eventually the deposits were depleted and by the turn of the century, when the above photograph was taken, the numbers had declined considerably. [14] In 1906 there were only 15, and the last of the original pioneer Shetlanders, William Harper, moved away in 1916. [11]

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Nola Sinclair and her husband for the opportunity to use her photograph as the subject of this article, and the Alexander Turnbull Library for permission to use scanned images of photographs in their collections.

References

[1] Hursthouse, Charles (1861) New Zealand, The "Britain of the South." 2nd Edition. London: Edward Stanford. p. 149. [Available online from Google Books]

[2] May, Philip Ross (1962) The West Coast Gold Rushes. Christchurch: Pegasus. 55p.

[3] Eldred-Grigg, Stevan (2008) Diggers, Hatters & Whores: The Story of the New Zealand Gold Rushes. Auckland: Random House New Zealand. 543p. ISBN 9781869419257

[4] Wood, Frederick Lloyd Whitfield (1971) Understanding New Zealand. Ayer Publishing. 267p. [Partially available on Google Books]

[5] Charleston, New Zealand. Wikipedia article.

[6] Wall, Ella & Lewers, Neville R. (ill.) (1939) Gold Rush at Charleston. Adventure - In the Old West Coast Days. in The New Zealand Railways Magazine, Volume 14, Issue 6 (September 1939) [Available online courtesy of the New Zealand Electronic Text Centre (NZETC)]

[7] Payne, Brett (2008) Fraternal Organisations. Photo-Sleuth, 3 August 2008.

[8] Anon (n.d.) Vorley, Herbert Henry. Auckland City Libraries Photographers Database.

[9] Extracts from Grey River Argus, West Coast Times, Nelson Evening Mail, Inangahua Times & Evening Post. Papers Past, Digital images of New Zealand newspapers and periodicals, from the National Library of New Zealand.

[10] Rackstraw, Tony (2008) Vorley, Herbert Henry. Early Canterbury Photographers, including South Canterbury and the West Coast, 22 August 2008.

[11] Faris, Irwin (1941) Charleston : its Rise and Decline. Wellington : A. H. and A. W. Reed. Reprinted 1980 by Capper Press, Ltd. [Extract courtesy of Nola Sinclair]

[12] Scots - The Late 1800s. Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

[13] Grey River Argus, Volume XVI, Issue 2259, 4 November 1875, Page 2. Papers Past.

[14] Butterworth, Susan M. & Butterworth, Graham (1997) Chips off the Auld Rock: Shetlanders in New Zealand. Wellington: Shetland Society of Wellington. 251 p. [Extract courtesy of Nola Sinclair]

[15] Grey River Argus, Volume XII, Issue 1142, 26 March 1872, Page 2. Papers Past.

[16] Grey River Argus, Volume XII, Issue 1337, 11 November 1872, Page 2. Papers Past.

[17] The Family of James Mouat Harper & Margaret Yule Anderson, on the Shetland Family History Home Page.

No comments:

Post a Comment